One of the double-edged swords of working in the humanities is that the news media doesn’t often report on the findings we publish in journals. Double-edged because on the one hand, we don’t get much popular exposure for the work we do, and on the other hand, that work doesn’t get grossly mischaracterized as tends to happen when the media reports on the findings of a particular study. So it’s not often that I see sloppy reports about study findings that actually relate to my academic interests.

But a recent article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology about reading and identification (though that’s not how the authors phrase it) has been getting (typically hyperbolic) headlines: Do Your Favorite Book Characters Change Your Life?, You are what you read, study suggests, ‘Losing Yourself’ in a Fictional Character Can Affect Your Real Life, etc. Each of those articles was more unhelpful than the next in figuring out what this study was actually claiming about reading and (implicitly) fiction, so I had to take a look at the study itself.

The results summary in the abstract gives a nicely succinct synopsis of what the authors are claiming about their research:

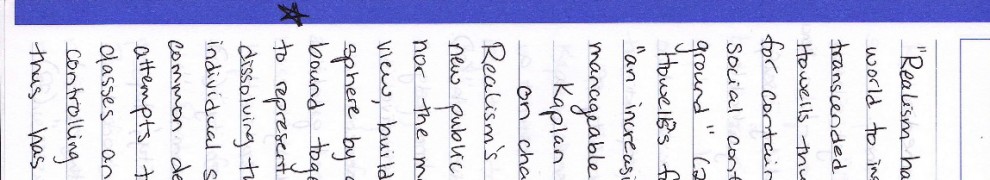

“Results from Studies 1–3 showed that being in a reduced state of self-concept accessibility while reading a brief fictional work increased—and being in a heightened state of self-concept accessibility decreased—participants’ levels of experience-taking and subsequent incorporation of a character’s personality trait into their self-concepts. Study 4 revealed that a first-person narrative depicting an ingroup character elicited the highest levels of experience-taking and produced the greatest change in participants’ behavior, compared with versions of the narrative written in 3rd-person voice and/or depicting an outgroup protagonist. The final 2 studies demonstrated that whereas revealing a character’s outgroup membership as a homosexual or African American early in a narrative inhibited experience- taking, delaying the revelation of the character’s outgroup identity until later in the story produced higher levels of experience-taking, lower levels of stereotype application in participants’ evaluation of the character, and more favorable attitudes toward the character’s group.”

There are a couple of things about this study I find interesting and potentially useful, and a great many more I have reservations about. First of all, this being social psychology, the terminology is significantly different than what I would tend to use. The authors focus on “experience-taking,” which they define as follows: “We propose that when experience-taking occurs, readers simulate the events of a narrative as though they were a particular character in the story world, adopting the character’s mindset and perspective as the story progresses rather than orienting themselves as an observer or evaluator of the character.” That definition has some implicit genre-limitations, since any number of fictional modes attempt to intentionally disrupt the reader’s ability to adopt a character’s mindset. But that aside, “experience-taking” seems to be very similar to Kenneth Burke’s idea of identification or consubstantiality, a definition I lean heavily on when I talk about fiction, identification, and reading here and here. According to Burke, “In being identified with B, A is ‘substantially one’ with a person other than himself. Yet at the same time he remains unique, and individual locus of motives. Thus he is both joined and separate, at once a distinct substance and consubstantial with another.”